|

|

Medgar Evers and the Early Fight for Civil Rights in Mississippi:

Information Sheet

Medgar Wiley Evers is a genuine American hero. As Field Secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi, he recruited members and organized branches, was an early leader in the fight for voting rights, and aimed at desegregating education, as well as the town square. He worked tirelessly, knowing that anyone who spoke out for freedom was a likely target in one of the most vicious and violent racist states.

Medgar Wiley Evers lives on in the hearts of NAACP members, in the minds of all freedom and justice loving peoples, and in the many monuments that bear his name. On June 28, 1992 a life-size bronze statue of Evers was unveiled at Medgar Evers Public Library in Jackson, Mississippi. In that city, a post office, and an international airport are named after him. There is a Medgar Evers College Preparatory School in Brooklyn, and a Medgar Evers Fine and Performing Arts Elementary School in Chicago.

Medgar Evers was born on July 2, 1925 in Decatur, Mississippi. His father worked in a saw mill and farmed, and his mother took in laundry and ironing. He lied about his age to get into the army and served in World War II in a segregated field battalion in England and France. After the war, he attended Alcorn College (now Alcorn State University), where he edited the student newspaper for two years and was entered into the Who’s Who in American Colleges. He married Myrlie Beasley from Vicksburg in 1951.

In 1952, while selling insurance to the poorest and most destitute African Americans in the delta region of Mississippi, Evers became a founding member of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership. In the fall of 1953, he decided to apply to the University of Mississippi Law School—a whites-only institution at that time–and he submitted his application in January 1954.

After being denied admission, he filed suit with the assistance of the NAACP, and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall was his attorney.

In December 1954, at the age of 29, Medgar Evers was hired as Field Secretary of the NAACP. Before taking the job, he and Myrlie discussed it and she agreed on the proviso that “we came as a package.” The two of them opened the NAACP office in Jackson.

After the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, NAACP Legal Defense Fund Director Thurgood Marshall called for a new round of litigation aimed at destroying Jim Crow segregation. In Mississippi, the white power structure aimed to oppose any attempts at desegregation. And on September 9, 1954 in Walthall County, 30 members of the local NAACP were called before a grand jury simply because they were advocating school desegregation.

A string of murders followed in Mississippi in 1955. Rev. George Lee, head of the NAACP branch in Belzoni was murdered on May 7, after he told authorities he would not stop trying to register voters. On August 13, Lamar Smith, 63 years old and a World War II veteran, was shot in full public view of many people in Brookhaven, because he too was urging people to vote. And on August 28, 14-year old Emmett Till was beaten to death. In order to investigate Till’s murder, Medgar Evers “dressed like a field hand,” in order to not raise suspicions and solicited potential witnesses, according to The Autobiography of Medgar Evers: A Hero’s Life and Legacy Revisited Through His Writings, Letters, and Speeches, by Myrlie Evers-Williams and Manning Marable. No one was ever convicted for any of these crimes.

As Field Secretary, Medgar Evers traveled the state, recruiting members to the NAACP, building branches, and fighting for voter registration. In a number of instances, he organized campaigns to pay the poll tax, so that one less hurdle stood in the way of voter registration.

At a Men’s Day program at a church in Jackson in 1962, he said: “As Negro Americans living in Mississippi today, it is imperative that we put forth extra effort to accomplish the desired goals of freedom for all…We must do our best. It is necessary that we become a part of this worldwide struggle for human dignity …Some of the signs that are most encouraging are the demonstrations in Africa, which are bringing about … independence…”

Mass demonstrations by students and young people against Jim Crow segregation broke out again in Jackson in early 1963. When the Mayor went on television to call for an end to the protests, Medgar Evers appealed to the FCC under the “equal time” provision and won 17 minutes to publicly make the case for integration and equal rights—a first in Mississippi history. On May 28, while speaking at a local AME church, he called for a “massive offensive against segregation.” And on June 1, 1963 Medgar and NAACP national executive secretary Roy Wilkins were arrested on a picket line at a Woolworth’s store in Jackson.

Just 11 days later, Medgar Evers was assassinated by a white supremacist coward, who hid in bushes across the street and shot the valiant NAACP leader on the doorstep of his home. The killer eluded conviction until 1994, when he was finally convicted and sent to prison for life.

Medgar Wiley Evers is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. After his death, his wife, Myrlie, moved to California with their three children and eventually remarried. She became national chair of the NAACP board of directors in 1995, and helped save it from suffocating debt. She has just recently moved back to Mississippi, and is participating in nationwide events to honor her martyred husband.

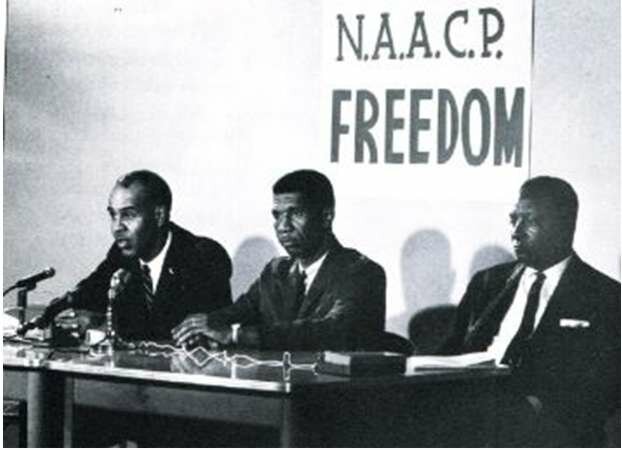

NAACP President Roy Wilkins (Left) and Medgar Evers (Center) in 1963

______________________________________________________________

The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission was a state-financed agency founded in 1956 with the Governor as its nominal head. It wrapped itself in the language of “states’ rights,” but its purpose was to oppose the civil rights movement in that state, and to protect Jim Crow segregation and the monopoly white people had over voting rights. It acted as an “intelligence” agency: hiring investigators, infiltrating civil rights organizations, and collecting personal information on NAACP members and other civil rights advocates.

The Commission kept tabs on Medgar Evers and when Byron de la Beckwith went to trial in 1964 for his murder, the state-funded Sovereignty Commission assisted the killer’s lawyers. Further, two Jackson policemen lied under oath during that trial, providing Beckwith with a false alibi until it came apart in 1994.